Poppy was an impulse acquisition. I had researched and decided on five breeds for our backyard chicken project. I’d bought the buff Orpington, barred rock, and Easter egger in Arroyo Grande and was told the golden-laced Wyandotte and Rhode Island Red (RIR) would arrive the following week.

I called a feed store in Paso to see if I could get the RIR and golden-laced chicks there. “Yes, we have some golden-laced Wyandottes,” I was assured. I drove to pick up my fourth chick. I’d scrounge up the common RIR from another store.

Located next to the glass door entrance, the tiny fluffballs were being blasted with wind as customers entered. The chicks were flying frantically against the sides of their wire cage. Clearly, they were not the pretty little chipmunk-marked golden-laced that I’d wanted, but the silver-laced variety.

But how could I not remove one of these chicks from this hostile environment and bring it home to my cozy brooder? I paid for Poppy and drove home to introduce her to her three sisters.

Poppy was different from the start. She was high-strung. She dominated the other chicks running over their backs. Poppy gave meaning to the term “the pecking order.” Within three weeks, I had the five breeds I’d originally wanted (Poppy made six) and a larger brooder, but Poppy continued to bully. At three weeks she prevented Daisy from eating and drinking and Daisy’s health was deteriorating.

I consulted books and articles. I asked for advice on backyardchicken.com’s forum. I e-mailed friends to see if someone would take her off my hands. “Cull her,” was the common chicken expert advice.

At my wits’ end, I called Diana Duncan at our treasured Homeless Animal Rescue Team (HART) shelter.

“I can’t take it any more!” I told her. “She’s a Cruella DeVille!”

She sympathized, then put me in touch with Linda and Bud Hotchkiss, who know birds of all kinds. Bud patiently listened to my story, assuring me that when Poppy was old enough to “free range,” he would take her, whether or not she was a hen or rooster.

“We don’t eat our roosters,” he told me. The end was in sight! I set up a second brooderand Poppy was put in solitary confinement until old enough to be re-homed.

In the month that Poppy was isolated, I handled her daily. When the others were moved to their permanent henhouse, I let her loose outside the pen where she followed me around the yard as I gardened. I began reintroducing her to the other pullets, starting with an hour a day, increasing until she eventually could be permanently housed with her flock again.

Why would I bother to keep this temperamental hen? All of us, who have raised or worked with kids and pets, know that there is something special about the “difficult one.” They challenge us to be our patient and creative selves and sometimes reward us with sweet success.

Poppy has grown into a strikingly beautiful hen. She is still the crankiest of the lot. She no longer chases the others, but will peck them when they invade her territory, occasionally blindsiding them while they eat or otherwise engage in innocent activity.

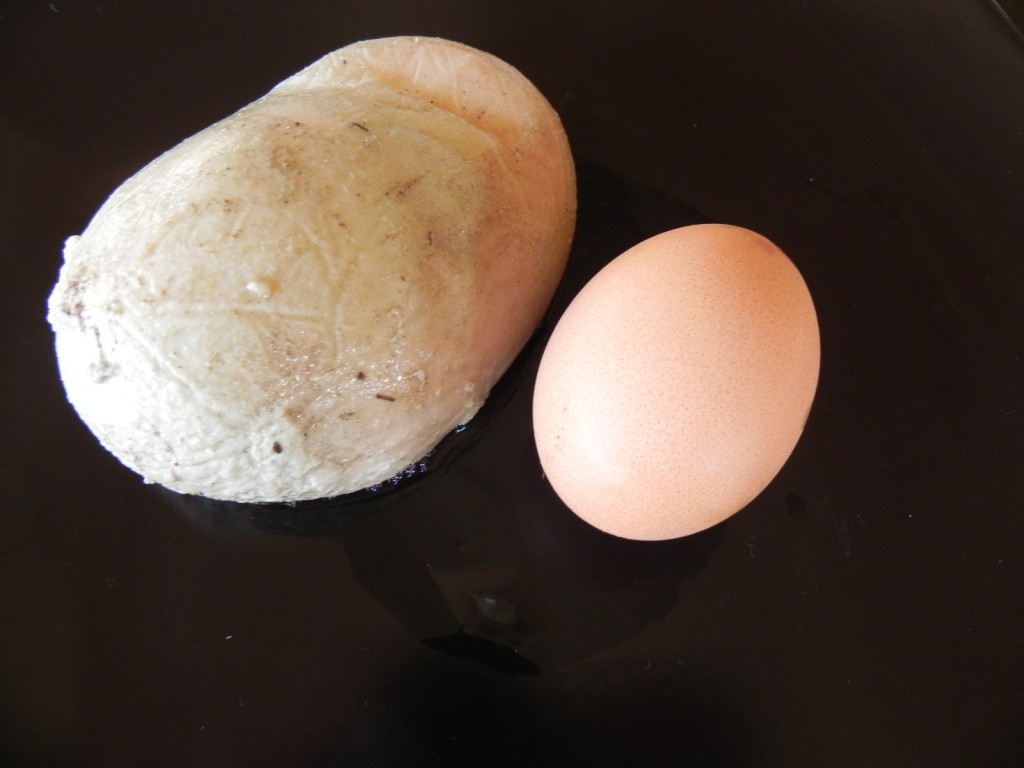

To us, her behavior appears to be cruel, but odds are, it is simply evidence of the “pecking order.” If we remove Poppy, another hen will take charge. Our hope is that Poppy, as a way of redeeming herself, will be our best egg layer.

This article was first printed in The Cambrian, http://www.sanluisobispo.com/news/local/north_coast/story/853292.html